Today, more than ever, innovations in life sciences and advancements in healthcare are dependent on data use. Despite the acceleration of healthcare digitization during the pandemic, which not only increased the volume of health data available but also solidified its crucial role in care delivery, disease prediction and diagnosis, medtech innovation, and patient outcomes, considerable gaps persist.

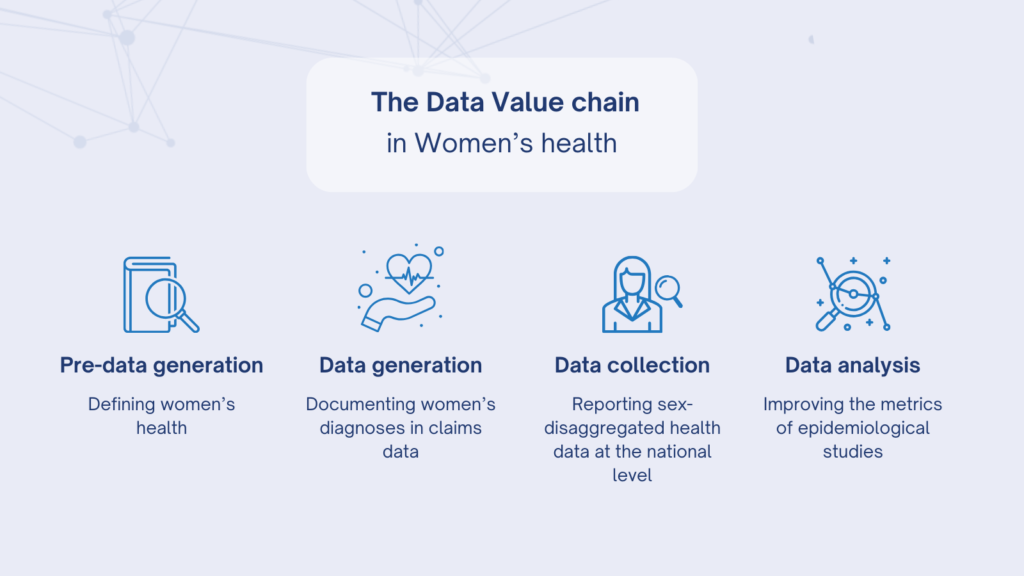

A notable illustration of these significant gaps is evident in women’s health, where disparities can be observed across the entire data value chain. This includes the initial definition of women’s health (pre-data generation), diagnosis (data generation), national level tracking (data collection), and the global interpretation of data into insights through epidemiological studies (data analysis).

These discrepancies in data have an impact on global health outcomes for women, creating gaps in the insights that inform decision makers, research design, investment decisions, and development pipeline priorities.

- Definition of Women’s Health

One of the key lessons I have learned from the various events, podcasts, and panel sessions organized by ECHAlliance within our EU projects is the critical importance of data quality in improving healthcare outcomes. However, “women’s health” often lacks a clear, comprehensive definition. Historically, women’s health was largely defined as “reproductive health.” Nowadays, the scope has broadened to include a wider range of conditions such as cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and less-studied areas like Alzheimer’s disease.

- Documenting women’s diagnose

For every case of women’s health conditions that is diagnosed, it’s estimated that four remain undiagnosed. In contrast, for men’s health conditions, the ratio of diagnosed to undiagnosed cases is approximately 1.5 to 1. This disparity suggests underlying issues in women’s health data, potentially due to biases in care delivery. Implicit biases related to race, ethnicity, gender, and other characteristics are linked to diagnostic uncertainty. Furthermore, medical education and training often lacks comprehensive coverage of women’s health issues, contributing to these biases. “Out of 112 internal-medicine residency programs reviewed in a 2016 study, approximately 25 percent did not include menopause in the core curriculum, 30 percent did not include contraception, nearly 40 percent did not include PCOS, and more than 70 percent did not include infertility.”

- Sex-disaggregated health data matters

The global collection of women’s health data is unbalanced in both quality and quantity. In 2020, less than 10% of countries reported on women’s access to contraception, affecting our understanding of maternal and child health, maternal mortality, and sexually transmitted infections. While data on contraceptive use, often limited to married women, has improved, less than 5% of countries provided information on menstrual material usage, a vital indicator of public health and gender equity. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 76% of high-income countries reported case data by sex, compared to only 37% of low-income countries. This disparity in sex-disaggregated data limits insights into disease prevention and the development of effective health interventions, leaving an incomplete picture of global women’s health, especially in lower-income countries.

- Improving the metrics of epidemiological studies

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD), the most comprehensive observational epidemiological study, covers 204 countries, 369 diseases and injuries, and 87 risk factors. It is considered a crucial tool for understanding global healthcare trends. However, it may not fully capture women’s health needs. An analysis using the GBD tool revealed that while nearly 60% of prevalence data is attributed to female-specific diseases like maternal health and menopause, these conditions account for less than 25% of disability-adjusted life years in women’s health. This suggests that traditional health metrics might not accurately represent the impact of female-specific conditions. Conditions like menopause, infertility, dysmenorrhea, and endometriosis cause significant disruption and distress, often understated in GBD metrics. For instance, women with endometriosis face substantially higher healthcare costs and a delayed diagnosis, especially among Black women.

In conclusion, this lack of data not only creates bias in understanding the true extent and nature of women’s health conditions but also limits the specific opportunities for innovation in women’s health and in the life sciences field more broadly, benefiting society as a whole. At ECHAlliance, we are committed to addressing this challenge. Our participation in the 9th edition of the Science Summit at UNGA78 in New York last September and our recent launch of the Thematic Innovation Ecosystem in Women’s Health, as well as at dedicated session during the upcoming Digital Health and Wellbeing Summit in February 2024 underscore our dedication to advocate women’s health. Keep an eye out for more updates and expert contributions in this critical area.

Resources

Burns D., Grabowsky T., Kemble E., and Pérez L. “Closing the data gaps in women’s health”, McKinsey & Company (2023)

Kemble E., and Pérez L., Sartori V. Tolub G., Zheng A. “Unlocking opportunities in women’s healthcare”, McKynsey&Company (2022)

Caroline Criado Perez, “We need to close the gender data gap by including women in our algorithms”,Time (2020)