Environmental health sciences identify and characterise a range of environmental exposures and their associated risk for disease, with numerous research and innovation projects aiming to inform the development of interventions, including recommendations, guidelines, and policies for mitigating exposure.

In my role as Innovation Project Manager for ECHAlliance – The Global Health Connector, I have been working on two great examples of such projects, K-HEALTHinAIR project and BRAINTEASER project. K-HEALTHinAIR aims to increase knowledge about chemical and biological indoor air pollutants affecting human health, and to provide solutions for more accurate monitoring and improvement of indoor air quality. BRAINTEASER, develops models to evaluate diagnosis/prognosis risk profiles in relation to environmental pollutants and to inform possible correlations and influences. The contribution of both these projects in advancing evidence of the linkages between environment and health through data was recently discussed during the 5th Digital Health Society Summit.

Now, looking at the societal impact of environmental health science, it is important to note that interventions only serve to mitigate exposures and prevent disease if they are effectively disseminated, adopted, implemented, and sustained. Fewer than 50% of clinical innovations ever make it into general usage. According to estimations, 80% of medical research dollars do not make a public health impact for various reasons. If only half of clinical innovations ever make it to general use, society’s return on investment for each medical research dollar is diminished even further. Moreover, there is an enormous time lag between clinical research and practice (estimated to 17 years in the field of healthcare). This time lag can be substantially longer for environmental health evidence to result in changes to policy and practice.

Recognition of the need for research that more directly impacts public health has broadened the academic mindset somewhat, from an exclusive emphasis on efficacy studies to more broadly generalisable effectiveness trials. However, such trials in and of themselves provide little guarantee of public health impact. Research-supported resources seldom remain at local sites to support continued use of even successful interventions; there is typically little institutional memory for the intervention, and no technology transfer. Moreover, evidence-based practices often have characteristics that make unassisted translation into practice unlikely, especially if the intervention requires incorporating a change in a routine. Many factors can impede evidence-based practices’ uptake, including competing demands on frontline providers; lack of knowledge, skills and resources; and misalignment of research evidence with operational priorities can all impede uptake.

There is clear need to develop specific strategies to promote the uptake of evidence-based practices of environmental health research, into general usage.

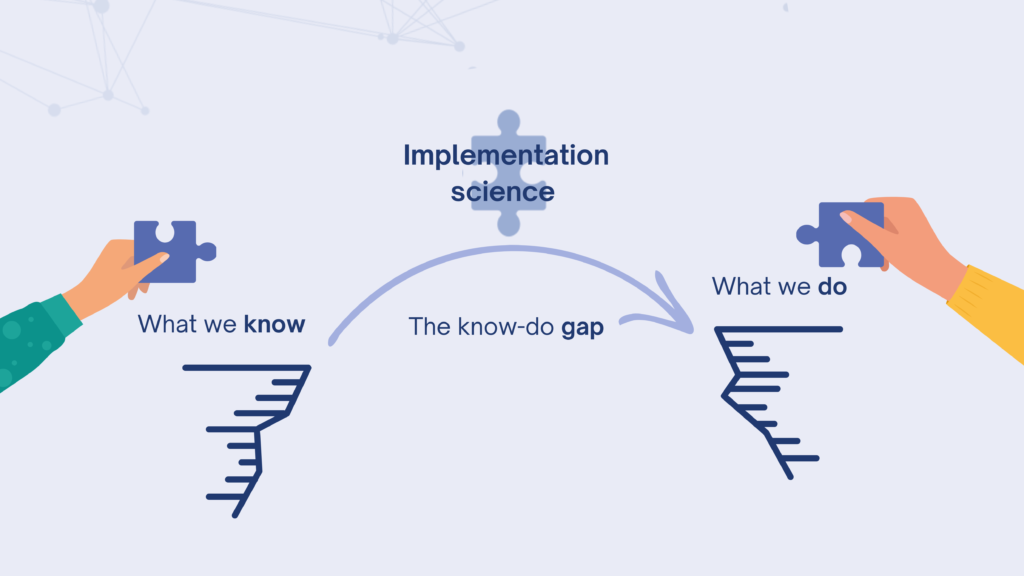

This is where implementation science steps in. As the scientific study of methods and strategies that facilitate the uptake of evidence-based practice and research into regular use by practitioners and policymakers, implementation science seeks to systematically close the gap between what we know and what we do (often referred to as the know-do gap) by identifying and addressing the barriers that slow or halt the uptake of proven health interventions and evidence-based practices.

Recommendations for incorporating implementation science include:

- applying implementation science frameworks to understand multilevel barriers and processes,

- co-creating tailored implementation strategies with key stakeholders to overcome barriers,

- measuring implementation outcomes of the strategies analysed (e.g., adoption, feasibility, fidelity, and sustainability

- analysing which, how, and why implementation strategies work.

Stakeholders (e.g., implementing individuals and organizations, including communities and policy makers) are crucial throughout, across all four approaches. The success of these approaches relies on meaningful engagement, trust, and collaboration. For example, K-HEALTHinAIR project establishes a robust and lasting Permanent Stakeholders Community, which will play a pivotal role in offering guidance and direction to the project consortium, actively participating in a series of consultation activities. Another example is the BRAINTEASER project, which is establishing a Community of Practice, a collaborative space for stakeholders interested in using AI and other digital tools to help manage these conditions.

Environmental health research can further advance disease prevention by fully integrating the concepts, methods, and findings of implementation science into its agenda, envisioning a more comprehensive flow from research to practice that maximises the use of scientific discovery and supports the mission of promoting healthier lives.